What makes a great place to live? Answer: it’s not a shopping plaza

by Simon Jenkins – The Guardian

The best place to live in Britain today is Salisbury. So says the Sunday Times. The Office for National Statistics disagrees. It says the best place is Farnborough. No, says the Royal Mail, it is Winchester. The Provident says it is Worcester. The Halifax says it is Stornaway. And so it goes. This is listicle season, and not a magazine is without some daft “survey” of topographical superlatives. Each year groups of travel editors get together over a good lunch, with a road atlas and contented sponsor to hand.

Salisbury’s award appears to be in compensation for last year’s novichok nightmare. To be free of novichok is clearly a marketing asset, but it is hardly a standout virtue. Other criteria include a low crime rate, good schools, transport links, air quality, nice buildings and friendly neighbours. The one thing these lists have in common is that nobody agrees. Apparently if you ask most people the best place to live, they say their home. Good for them. There is nowhere like home. But dig deeper and the trends in modern “liveability” are intriguing.

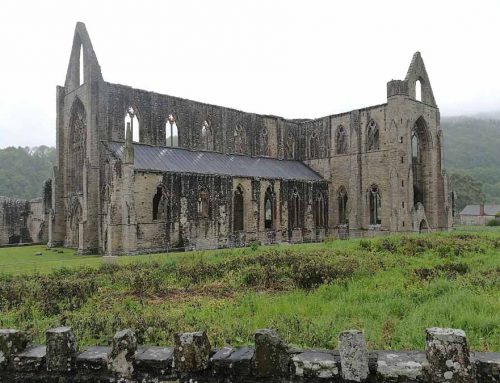

There is no question, the greatest asset to any British town or city is a medieval cathedral. The burning of Notre Dameshowed the intense emotional bond between these buildings and those living in their shadow. This seems unrelated to faith. Philip Larkin viewed old churches as left to “rain and sheep”, with “a few cathedrals chronically on show”. Today Salisbury, York, Norwich, Chichester, Canterbury and Winchester are soaring in popularity, rarely out of the top 10. They are the car factories and steelworks of the modern service economy.

There is no question, beauty sells. Estate agents reckon that a cathedral can add 10% to house values. Handsome Edinburgh has been outdoing Oxford and Cambridge for house-price inflation. Retirement towns also fare well, with Harrogate, Christchurch, Tunbridge Wells and Brighton regularly featuring. So do the predictably appealing resort villages of Oxfordshire’s Charlbury, Suffolk’s Woodbridge and Cumbria’s Cartmel.

More interesting are the newcomers to these lists, towns that have fought back against planners who want to “doughnut” them, by removing their high street shops to hypermarkets and malls on their bypasses – as at Ely and Penrith. This is state-supported, outright retail murder. Towns such as Farnham, Beverley, Monmouth, Ludlow and Kendal have retained their liveability by refusing to capitulate to the planners – whose idiocy is now apparent as many bypass centres fail because of online shopping.

A recent BBC programme hit this nail on the head with a comparison between two Cheshire towns, Northwich and Altrincham. The former had spent £70m on a huge shopping complex called Barons Quay, more appropriate to Dubai, hoping to kill off its attractive but ailing neo-Tudor town centre. Almost no shops moved to it. The town has a crippled high street and a mostly vacant dinosaur.

Nearby Altrincham did the exact opposite, and must already be heading for a best-town listicle. It took hold of a similar ghostly centre and pondered what might draw people back to its streets. It set up market stalls and gradually colonised an old hall. It revived its economy from the bottom up, and with total success. Lettings in five years have gone from 30% vacancy to 10%. The market now employs 150 people. Altrincham is alive once more. The moral is that a town’s appeal – and thus its prosperity – lies in how we experience it, not in how much money a developer can extort from us. Start with that motive, and the answer will be none.

This makes the other candidates on the Sunday Times list more instructive. The regional “winners” are truly eccentric, formerly run-down neighbourhoods whose very decay held the key to their regeneration. In Edinburgh, it is not the New Town but the depressed docks of Leith. In Manchester it is the mill district of Ancoats; in Bradford it is the mill at Saltaire; and in smart Gloucestershire, it is scruffy Stroud. London’s “winner” is even more bizarre. Best in town is no longer Notting Hill or Islington or even fast-rising Shoreditch. The shortlist includes Leyton, East Finchley and Crystal Palace, and the winner is, believe it or not, the Isle of Dogs. Why the Isle of Dogs? The answer is a derelict church converted into a “rustic boho watering hole”, called the Hubbub. This is no joke. These days it is clear that hipster rustic boho watering holes are not the transient emblems of a surface gentrification. They are the indicator species of future prosperity. They are the Salisbury cathedrals of the new urbanism.

Writers such as Richard Florida and Richard Sennett have long championed “creative congregation” as holding the key to urban revival. New ideas and new networks require what cities always supplied – casual locations, informal places where ideas could be exchanged face-to-face. They specifically do not need open spaces and modern offices, those enervators of creativity. They need flexible premises, low rents and private corners for casual stimuli. The so-called Shoreditch effect is real.

I recently visited perhaps the most desperate city centre in Britain, the virtually empty Victorian downtown of Bradford. Two years ago saw the arrival, glowing in its centre, of Sunbridge Wells, a subterranean warren of craft beer hangouts, gin bars and studios, buried in hillside tunnels and surrounded by boarded-up shops and warehouses. It is a true test bed for the Florida/Sennett thesis. When Sunbridge Wells makes it into the listicles, a new urbanism is born. Home brewing and holistic medicine may not be the Salisbury cathedrals of tomorrow. But the message is the same. Always respect the old fabric of a city, be it Notre Dame or a tumbledown Bradford cellar. The past is the one sure investment in the future.